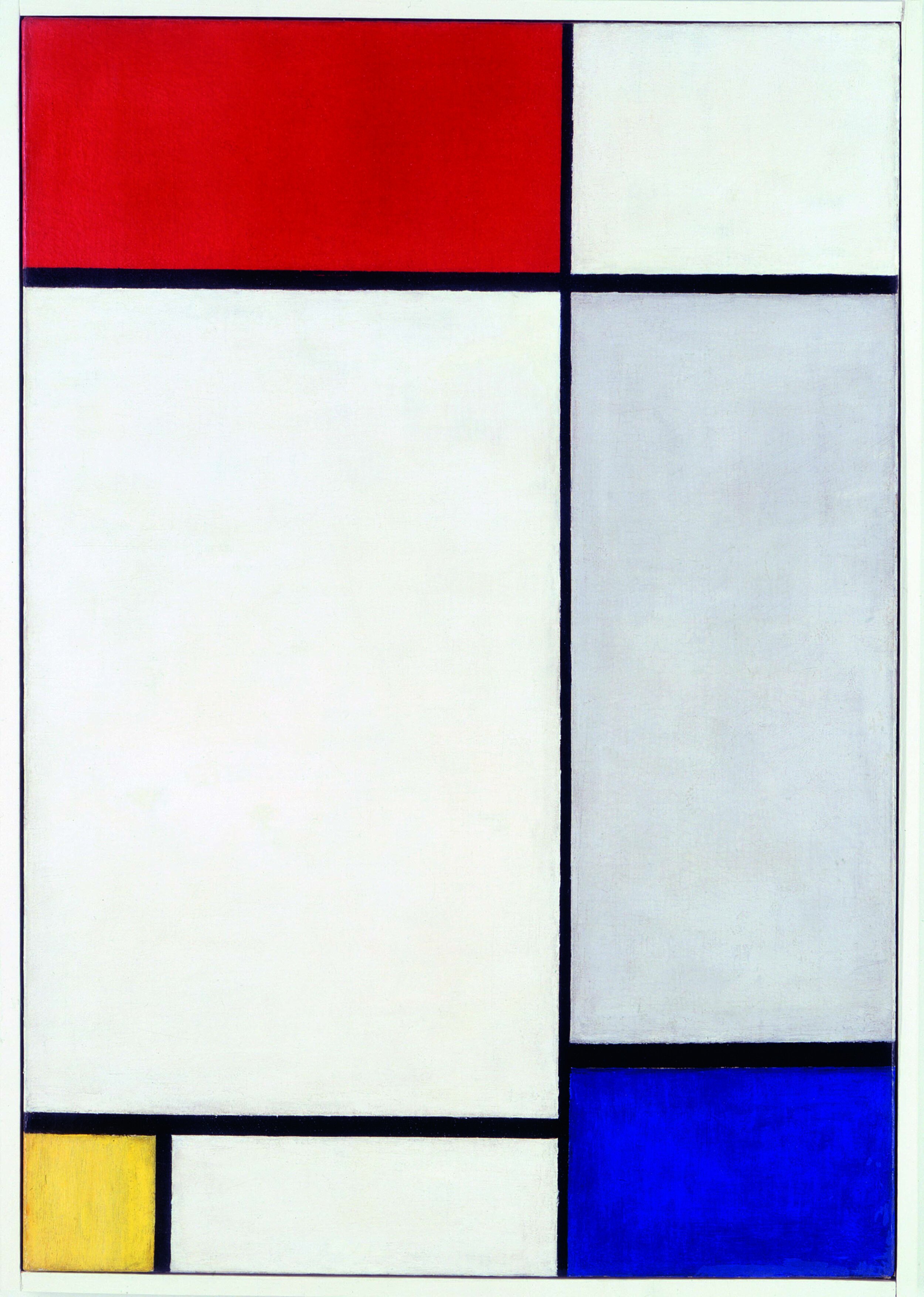

Like Kandinsky also, Mondrian was linked to, and affected by, the rationalism of 1920s architecture and design, which believed it could reform human nature through rational control of the environment. His paintings act like metaphors for a rationally balanced world: a huge red square can be balanced by a well placed, but much smaller yellow and blue to achieve what he called ‘dynamic tension’. But over the years the idea of metaphor seemed to fade, and he came to think of his paintings not as images of an unseen reality, but part of reality, part of the urban environment that he believed to be shaping human spiritual evolution.

In the 1920s he coined a term for his painting: neo-plasticism. It emphasises the plasticity, the physicality, of the work of art: the painting is not a traditional icon referring to a reality beyond, but a reality in itself. In the earlier images the edges are blurred, as if to show a separation between the image and the world of the viewer. But in the later work the lines continue to the edge of the canvas and there is no frame, suggesting the work continues into the surrounding area of wall. Indeed, at times in his writings you get the feeling that, if you peeled back the surface of the world, with all its confusing multifariousness, there underneath you would see something akin to a Mondrian painting.

Utopianism implies that perfection can be reached, and all other possibilities superseded. Hence the exclusion of anyone else’s work from his studio. And his paintings work best when they are exhibited with each other, and no one else’s. In a normal art gallery you see a Mondrian next to a Van Doesburg, and you realise that energy can be explosive, and not contained (the two artists fell out over the use of the diagonal). Put one next to an expressionist, surrealist or war artist and you are forcibly reminded of all the aspects of humanity that Mondrian is skating over.

But in this exhibition, the largest collection of Mondrians seen in the UK, the rows of related but subtly varying paintings create a delightful environment that invites relaxed, serious contemplation. There is a lovely set of three works from 1920, reunited from various galleries; and of course a great room of the 1920s classics.

In the end it is a vision that fails to take account of the true ills of human nature, just as its architectural counterpart failed to change human nature by changing his environment. But the vision itself is beautiful, as are the works.

Mondrian and his studios

Tate Liverpool, until 5 October 2014

Mondrian was a utopian idealist and, like many such, he was a mixture of barmy eccentricity and deep seriousness that generated great affection for him personally, as well as great works of enduring beauty.

You feel his presence in the reconstruction of his Paris studio, which forms a key feature of this exhibition. There is a shrine-like sense to this place where he developed all those classic arrangements of black lines on white backgrounds, punctuated by squares and rectangles of primary colours, beautifully and intuitively balanced by eye.

The feeling of Mondrian’s presence in the studio is partly due to there being nothing there by anyone else. If he owned works by other artists, he put them in a different place. His studio – and this is the theme of the exhibition – was part of his art. It is like a three-dimensional version of his painting, carefully crafted to be austere, peaceful, almost monastic. Areas of pure colour, varying in size, punctuate the white walls. The furniture too is painted or upholstered in black, white and pillar-box red.

Stories of his eccentric behaviour abound. In his desire to imprint human rationality on nature, he is supposed to have gone for walks through the woods, making precise ninety-degree turns rather than follow the natural path. He is reported to have swapped seats in a New York cafe so that he could look at the buildings rather than the plants. He wore a shirt and tie under his painting overalls, looking like an undertaker, but danced to jazz in his studio as well as in nightclubs.

Yet his painting is deeply serious. Like that other great pioneer of non-representational painting, Wassily Kandinsky, Mondrian was a Theosophist. They believed that humanity was evolving not just physically but spiritually, and it was through the contemplation of art that the human soul would be enlightened and perfected.

[This review was first published in Third Way magazine, Summer 2014]

Image credits:

Reconstruction of 26 Rue du Départ, Paris based on 1926 photo by Paul Delbo.

Photograph

© 2014 STAM, Research and Production: Frans Postma Delft-NL. Photo: Fas Keuzenkamp

© 2014 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust c/o HCR International USA

Piet Mondrian, 1872-1944

No. VI / Composition No.II 1920

Oil paint on canvas

997 x 1003 mm

Tate. © Tate Photography, 2014.

© 2014 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust c/o HCR International USA

Piet Mondrian, 1872-1944

Composition with Red, Yellow and Blue 1927

Oil on canvas

750 x 520 mm

Museum Folkwang, Essen.

© 2014 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust c/o HCR International USA