Henry Moore

Review of the exhibition at Tate Britain, until 8 August 2010

First published in Third Way (April 2010)

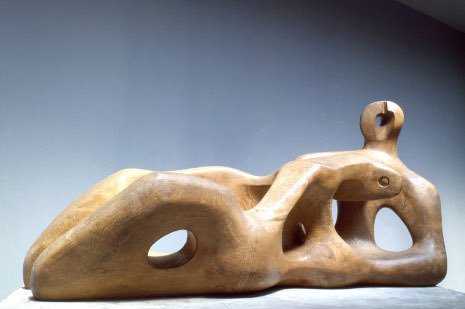

Henry Moore: Reclining figure (1939; elmwood; 94 x 200.7 x 76.2 cm; Detroit Institute of Arts).

Copyright The Henry Moore Foundation

The curators of this exhibition have an overt agenda. They argue that the huge popularity of Henry Moore after the Second World War had the effect of domesticating his work and blinding us to Moore’s dark side. They want to re-establish that Moore’s oeuvre was, in the words of Bryan Robertson, ‘anything but gentle’.

It took me a while to be convinced of the argument, partly because it depends on the commentary rather than the works. The exhibition itself contains many of the familiar, warmly human images of mothers and children, and ends with a glorious room of four huge reclining figures in elm wood.

Even the wartime drawings of figures sheltering from the Blitz in the underground, adduced here as an example of the artist’s edginess, seem to me perfectly sympathetic. The drawing of two sleeping figures, one with a hand innocently placed on the chest of the other in what is obviously a long and habitual closeness, seems engaging and comforting.

Nevertheless, the curators have got a point. With Moore’s success he came to be seen as the avuncular supplier of comforting human forms set in a landscape, or attractively tactile bronzes set in almost every urban space in the western world. And in some people familiarity certainly bred contempt.

Moore, however, remained a deeply serious artist who claimed that a good work of art is ‘the expression of the significance of life’ and ‘a stimulation to greater effort in living’. There is undoubtedly a dark, brooding side to his work, reflecting the angst of an age that is caught between hope and despair. On the bright side is the modernist thrill of freedom from old meanings and old forms, the optimism of creating a new humanity. Set against that are the darker implications of Darwin and Freud for what it means to be human, coupled with memories of the First World War as proof of what human beings are capable of. Moore himself served in the trenches, being gassed in 1917, and finding himself one of only 52 survivors from the original 400 men in his battalion.

Like many of his contemporaries Moore found a vocabulary for these sensibilities in non-Western art, from African, North and South American, Oceanic and palaeolithic sculpture. These meshed well with a Surrealist-inspired creation of forms that resisted rational explanation. He created sculptures, particularly in the early 1930s, that were at times, with their distorted, hornlike heads and inscribed markings, unsettling and threatening, and at other times defiantly hermetic.

What is odd about the argument of the exhibition, however, is that it invites us to look at the works more naturalistically than we have been taught to. In previous generations we had been encouraged to engage with sculptural form as an end in itself, divorced from naturalism and narrative. As Moore himself wrote in 1930 the sculpture that moved him most ‘has a life of its own, independent of the object it represents’. This exhibition invites us to look at the works much more literally as representations: these body parts are direct metaphors for a broken humanity, and these holes are all Freudian.

Of course, there is nothing funnier than watching art historians who are sure they have scented sexual references: no hole and no vertical line, however innocent, is allowed to go unmasked – and of course, there are a lot of holes in a Henry Moore.

Nevertheless, even if at times the interpretation seems a little strained, it is interesting to see scholars rediscovering what they term the ‘abject’ in Moore’s depiction of the human, the brokenness, the mourning, and the focus on non-rational emotion. The search for meaning in a modernist world was neither triumphant nor triumphalist.

And yet, undercutting the argument of the exhibition, Moore has a redemptive side. While the Continental Surrealists created a closed world of sexual fantasy and hopeless anxiety, English Surrealists such as Moore and Paul Nash had a more romantic, almost pantheistic side to them, and tended to point outwards, towards a hope located in nature or in the humanity of the figure.

For all the edginess that this exhibition seeks to underline, it is still very life-affirming. Human beings are treated with nobility. The sculptor glories in the beauty of natural materials, which become a force in determining the final form. And the overt connections of figure and landscape create an atmosphere that is at least open and hopeful.